Traditional psychiatry often focuses on symptoms but misses one of the core drivers of “treatment resistance” in depression, PTSD, and TBI: chronic neuroinflammation and disrupted blood flow in critical brain networks like the prefrontal cortex. For many Veterans and first responders, that biology helps explain why medications alone so often fall short—and why they feel like the system is failing them, not the other way around.

How trauma, PTSD, and TBI drive neuroinflammation

Traumatic brain injury, even at mild levels, is now clearly linked with a long-lasting inflammatory response in the brain.

- Reviews of TBI show that mechanical injury is followed by secondary cascadesmicroglial activation, cytokine release, and oxidative stress—that can persist for months to years after the initial event.

- TBI roughly doubles to triples the risk of developing depression and PTSD, and patients with TBI plus PTSD or depression often show higher levels of central and peripheral inflammatory markers (for example, IL‑6, TNF‑α, IL‑1β) than those with TBI alone.

- PTSD and TBI often co-occur with chronic pain in Veterans (“polytrauma clinical triad”), and each condition is independently associated with heightened inflammatory signaling and worse functional outcomes.

Similar inflammatory patterns appear in mood disorders: people with major depressionspecially those with treatment-resistant depression—are more likely to show elevated inflammatory markers and may represent an “inflammatory subtype” of depression.

In other words, for a large subset of patients with chronic PTSD, TBI, and depression, there is real evidence of ongoing neuroinflammation—not just “chemical imbalance” or purely psychological distress.

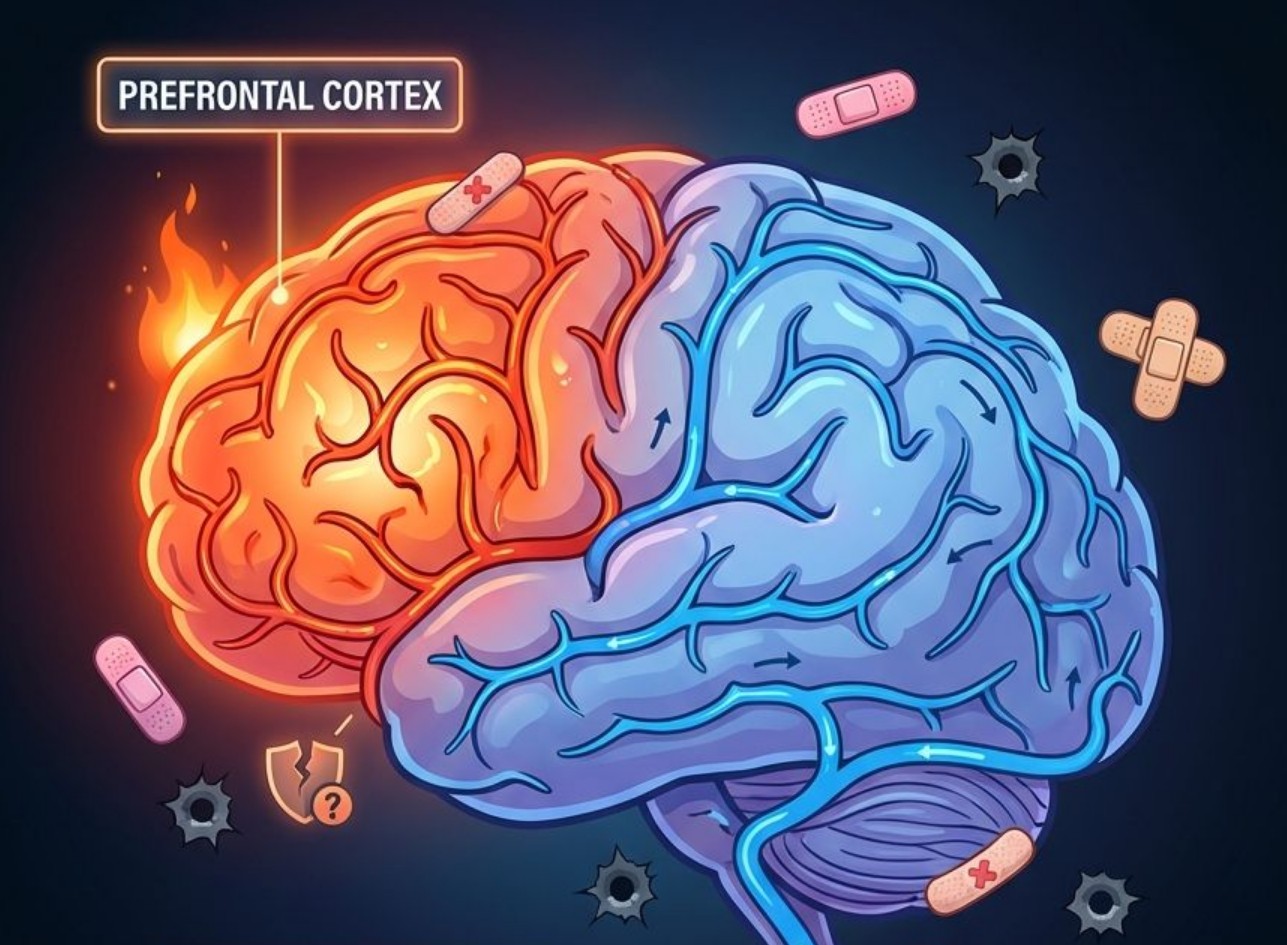

Neuroinflammation, blood flow, and the prefrontal cortex

The idea that “inflammation shuts off blood flow to the prefrontal cortex” is a simplification, but it reflects a pattern the literature supports:

- Depression and PTSD are associated with altered cerebral blood flow and disrupted self-regulation of perfusion, particularly in prefrontal and limbic regions.

- Cerebral blood flow self-regulation appears impaired in depression, with mechanisms involving endothelial dysfunction, microglial activation, and cytokine changes—key players in neuroinflammation.

- In TBI and blast-exposed military populations, neuroimaging studies show changes in white-matter integrity and functional connectivity involving prefrontal circuits, and perfusion abnormalities have been linked with symptom severity.

Taken together, these findings support the clinical observation that patients with chronic trauma and brain injury often experience:

- Emotional hijacking: Hyperreactive limbic circuits (amygdala, insula) combined with underactive or under-perfused prefrontal control systems.

- Impaired executive function: Difficulties in planning, decision-making, concentration, and cognitive flexibility tied to prefrontal and frontal–subcortical circuit changes.

- Persistent brain fog: Slowed processing, fatigue, and attentional lapses frequently reported after TBI and in PTSD/depression, with imaging correlates in prefrontal and temporal networks.

So while it is not yet accurate to say inflammation literally “shuts off” blood flow in a simple on/off way, there is solid evidence that neuroinflammation, vascular dysregulation, and prefrontal dysfunction travel together in chronic PTSD, depression, and TBI.

Why medications alone often fail

If part of the problem is an inflammatory, vascular, and circuit-level issue, it makes sense that simply adjusting serotonin or norepinephrine is not enough for many patients.

- Patients with treatment-resistant depression are more likely to show elevated C‑reactive protein (CRP) and cytokines, and higher inflammation is associated with poorer antidepressant response.

- Reviews of “inflamed depression” emphasize that standard antidepressants have limited impact on inflammatory drivers, and that inflammation may contribute to anhedonia, low motivation, and cognitive symptoms that persist despite adequate trials of medications.

- In TBI populations, depression, fatigue, and sleep problems frequently co-occur, and structural and functional imaging changes in key networks help explain why these symptoms often do not respond to traditional psychiatric algorithms alone.

This supports the core message of your post: many Veterans and first responders with chronic PTSD, TBI, and depression are not “failing treatment”—their treatments are failing to adequately target the biology driving their symptoms.

How interventional and brain-focused treatments fit in

Emerging evidence suggests that brain-focused and neuromodulation approaches may help by influencing both circuits and inflammation.

- Neuromodulation therapies such as TMS have been shown to reduce depressive and anxiety symptoms while also modulating inflammatory markers like IL‑1β, IL‑6, and TNF‑α in both animal and human studies.

- Repetitive TMS targeting the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, a key executive control region, can improve mood and cognitive function and is being explored partly as a way to normalize dysregulated prefrontal–limbic circuitry.

- Ketamine, used in treatment-resistant depression, has been associated with rapid symptom reduction and may exert some of its effects through anti-inflammatory and glutamatergic mechanisms; early studies have noted peripheral inflammatory changes in responders.

While more research is needed, these data align with a layered strategy: address neuroinflammation and circuit function while also working with trauma, cognition, and behavior—rather than relying on medications alone.

How Mind Spa Denver approaches “treatment resistance” differently

For Veterans, first responders, and others with complex trauma histories, Mind Spa Denver’s model reflects this integrated understanding of brain health.

- Brain- and body-informed assessment: Evaluating PTSD, TBI, depression, chronic pain, and sleep together, with attention to blast history, injury, and systemic inflammation rather than siloed diagnoses.

- Interventional psychiatry: Offering TMS, ketamine-based treatments, and other advanced interventions to directly modulate prefrontal and network-level function in those who have not responded to medications alone.

- Trauma- and neurorehab-informed care: Combining psychotherapy, skills work, and somatic strategies with brain-focused treatments to address both the narrative and the neural circuitry of trauma.

From this lens, “treatment-resistant” is often a mislabel. In many cases, the patient is not resistant—the approach is incomplete. A physiology-aware strategy that accounts for neuroinflammation, perfusion, and network-level disruption offers a more accurate and hopeful framework for healing.

Works Cited

- Caplan, H. W., et al. Role of inflammation in TBI-associated risk for neuropsychiatric disease. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 2021.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12128916/ - Lozano, D., et al. Neuroinflammation in traumatic brain injury: A chronic response to acute injury. Brain Research, 2017.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6057689/ - Xing, J., et al. Cerebral blood flow self-regulation in depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 2022.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0165032722000635 - Zhang, C., et al. Neuroinflammation mechanisms of neuromodulation therapies for mood and anxiety disorders. Translational Psychiatry, 2023.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41398-022-02297-y - Walker, A. K., et al. Advancing an inflammatory subtype of major depression. Biological Psychiatry, 2025.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12282100/ - Powell, C. S., et al. Peripheral inflammatory effects of different interventions for depression. Psychological Medicine, 2022.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12282100/ - Croarkin, P. E., et al. Biological correlates of treatment resistant depression. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 2023.

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1291176/full - Tang, V. M., et al. Brain-based correlates of depression and traumatic brain injury. Frontiers in Neuroimaging, 2024.

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/neuroimaging/articles/10.3389/fnimg.2024.1465612/full - McFadden, A., et al. Chronic Pain, TBI, and PTSD in Military Veterans. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics, 2018.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6026045/ - O’Neil, M. E., et al. Posttraumatic Stress and Traumatic Brain Injury: Cognition, Behavior, and Neuroimaging. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 2023.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10578246/ - Polusny, M. A., et al. Neuropsychological Sequelae of PTSD and TBI Following Military Deployment. Neuropsychology Review, 2012.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5032645/ - Institut Pasteur. Depression: the key role of neuroinflammation. 2024.

https://www.pasteur.fr/en/home/research-journal/news/depression-key-role-neuroinflammation