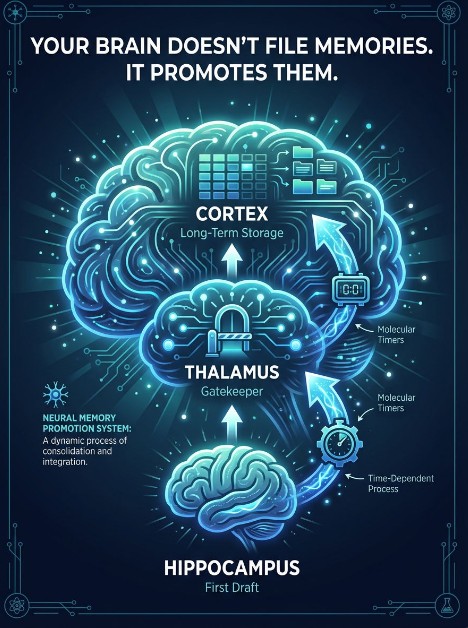

Most people think memory is made at the moment of learning. In reality, the brain continues “working” on a memory after the event, sometimes for days to weeks. During that window, many experiences fade while a smaller set consolidates into durable, remote memories.

A peer-reviewed Nature paper from Priya Rajasethupathy’s group (Rockefeller University) adds a mechanistic layer to this idea: long-term memory stabilization appears to be coordinated by a thalamocortical molecular program that unfolds in stages, using distinct transcriptional regulators as time-dependent “gates.” PubMed

This matters because in real-world clinical syndromes, the problem is often not “no memory formed.” Instead, the problem can look like:

Understanding when and where stabilization breaks down is a different question than how a memory is encoded in the first place.

Across decades of research, systems-level models of memory have emphasized that the hippocampus is essential for forming new episodic memories, while longer-term storage involves distributed cortical representations that evolve over time. The newer picture is less “handoff” and more “distributed negotiation,” where multiple brain regions participate in different phases of memory maturation.

A 2024 Neuron review from the same research group highlights that the thalamus and prefrontal cortex should be considered core contributors to this evolving, brain-wide process, not peripheral supporting actors. PubMed

In the Nature study, the authors created a behavioral paradigm in mice where multiple memories could be formed, but only some were maintained over weeks while others decayed. They then tracked circuit-specific molecular programs associated with whether a memory persisted. PubMed

The strongest claim in the paper is not simply “the thalamus is involved.” The paper reports that the thalamocortical circuit expressed multiple waves of transcriptional activity (cellular macrostates) that mapped onto memory persistence, and that a small set of transcriptional regulators orchestrated these programs in a time-dependent way. PubMed

Using targeted CRISPR knockout approaches, the authors report that these regulators:

Specifically (as summarized in the PubMed abstract):

If this staged model continues to replicate and generalize, it supports a clinically relevant distinction:

For many years, the thalamus was often reduced to a sensory relay. That view has been steadily changing. A major 2023 Cell paper showed that an anteromedial thalamus-to-cortex circuit can bias which hippocampal memories become stabilized at remote time, providing a plausible “selection and stabilization” function at the circuit level. PubMed+1

Putting the 2023 Cell findings beside the 2025 Nature findings suggests a convergent theme: the thalamus may participate in deciding what gets promoted into durable cortical storage, and the decision may be implemented through coordinated circuit activity plus staged gene-expression programs. This interpretation is consistent with the direction of the peer-reviewed literature, while still leaving open major questions about generalizability to humans and to clinical syndromes.

It is tempting to jump from “memory stabilization has stages” to “we can precisely edit memories.” The peer-reviewed evidence does not justify that leap today. What it does justify is a more careful framing of memory-related symptoms:

PTSD includes intrusive and recurrent re-experiencing of trauma-related memories. A long-standing clinical neuroscience perspective emphasizes that PTSD involves dysfunction in circuits that support contextual processing, including hippocampal–prefrontal–thalamic interactions. PubMed

There is also an active clinical research literature on targeting when memories are labile, such as during sleep-related consolidation or reconsolidation windows. For example, a 2022 open-access review discusses sleep as a potential intervention window for traumatic memory processing, including the concept of targeted memory reactivation. ScienceDirect

In real patients, memory complaints may reflect attention, sleep disruption, stress physiology, executive dysfunction, or mood symptoms, not only hippocampal encoding failure. PTSD neurobiology reviews emphasize heterogeneous mechanisms and circuit-level dysfunction, which is one reason symptom profiles vary and why treatment often needs to be individualized. PubMed+1

If you are dealing with depression, anxiety, PTSD, or TBI-related symptoms, memory issues often show up as:

This new line of peer-reviewed work suggests a helpful way to think about those experiences:

The brain has multiple checkpoints between “I experienced it” and “it became a durable, retrievable memory weeks later.” PubMed

That means interventions that improve sleep, reduce arousal, strengthen executive control, and improve circuit-level regulation may indirectly influence how experiences are integrated over time. This is a scientific rationale for multimodal care, but it is not proof that any single clinical intervention can selectively strengthen or erase specific memories.

At Mind Spa Denver, our clinical focus is interventional psychiatry for conditions where standard approaches have not been enough. If you want to discuss treatment options appropriate to your situation, schedule a consultation through the website.

Is long-term memory formed instantly?

No. Peer-reviewed neuroscience supports that memory stabilization unfolds over time and involves multiple brain regions. PubMed+1

What is “remote memory”?

In research, “remote” often refers to memories retrieved after longer delays (for example, weeks in animal studies), after systems-level reorganization has occurred. PubMed+1

Why does the thalamus matter for memory?

Recent peer-reviewed work supports a role for thalamocortical circuits in selecting and stabilizing memories over time, not merely relaying sensory input. PubMed+1

What are CAMTA1, TCF4, and ASH1L in this context?

In the Nature study, these were reported as time-dependent regulators that were required for memory maintenance across different phases (days versus weeks), without substantially impacting initial memory formation. PubMed

Does this research mean we can erase traumatic memories?

Not based on current peer-reviewed clinical evidence. The paper supports a staged stabilization model in mice, which is a foundational step, not an established human therapy.