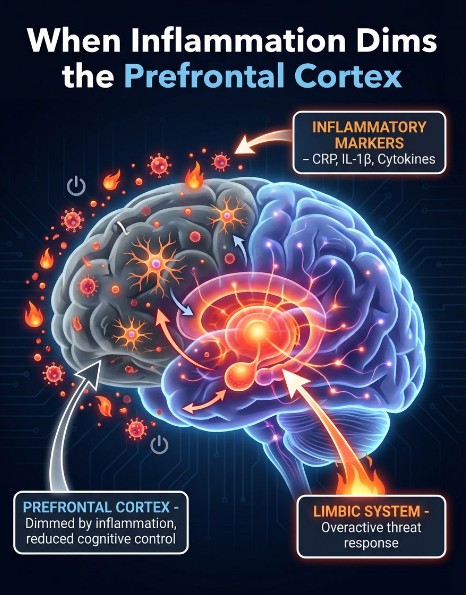

In psychiatry, we have long explained depression, anxiety, and PTSD through neurotransmitters, trauma learning, and stress physiology. Those frameworks still matter. But a growing body of peer-reviewed research suggests that for a meaningful subset of patients, chronic low-grade inflammation is not merely associated with symptoms. It may be contributing to a recognizable brain state that makes recovery harder: hypofrontality, meaning reduced efficiency, activity, or connectivity in the prefrontal networks responsible for cognitive control, emotion regulation, and flexible learning. PMC+2Frontiers+2

This matters clinically because a “dimmed” prefrontal system can look like treatment resistance. Patients may feel flat, foggy, fatigued, reactive, or unable to translate insight into durable change, even with good therapy and reasonable medication trials.

The prefrontal cortex is central to:

When prefrontal networks are underpowered or poorly connected, symptoms often cluster around:

Those patterns are commonly described in “inflamed depression” models that connect inflammation to specific symptom dimensions and neurofunctional changes, rather than treating depression as one uniform condition. ScienceDirect+2PMC+2

In depression, multiple lines of work connect higher inflammatory markers, including C-reactive protein (CRP), with measurable brain differences, including changes in functional connectivity within fronto-striatal and prefrontal networks. A widely cited study found that higher CRP was associated with reduced connectivity between ventral striatum and ventromedial prefrontal cortex, and that this reduction related to higher anhedonia. The same paper also linked inflammation-associated connectivity changes to psychomotor slowing. Nature+1

More broadly, narrative and translational reviews summarize converging MRI and biomarker findings suggesting that inflammation is associated with structural and functional alterations in circuits relevant to depression. PMC+1

A 2024 Frontiers editorial framing “When the prefrontal cortex network goes wrong” highlights neuroinflammation as a mechanism that can disrupt prefrontal network function across behavioral and psychiatric conditions. Frontiers+1

This is not a claim that inflammation explains every case. It is a claim that inflammation can be a meaningful contributor to prefrontal network dysfunction in a subset of patients.

Human psychiatry cannot ethically reproduce all mechanisms directly. Preclinical models help fill gaps.

Across stress-based animal models, chronic stress can activate microglia and inflammasome pathways, increase pro-inflammatory cytokines (including IL-1β), and impair synaptic strength and plasticity in prefrontal and limbic circuits. This pattern is consistent with a “turned-down gain” in frontal networks. PubMed+2PMC+2

A frequently cited preclinical study reported that microglial NLRP3 inflammasome activation mediates IL-1β related neuroinflammation during chronic stress, supporting a mechanistic route from stress to inflammatory signaling to behavioral changes relevant to depression. PubMed+1

If inflammation contributes to a hypofrontal state, treatment resistance becomes more understandable.

A peer-reviewed study in Brain, Behavior, and Immunity reported that people with treatment-resistant depression showed higher CRP levels compared with treatment-responsive and untreated depressed groups, supporting CRP as a marker associated with a more resistant course. PMC

Inflammation-linked depression is often described as featuring more prominent fatigue, anhedonia, cognitive symptoms, and slowed motor function. The CRP-connectivity findings described above directly map inflammation to reward and motor-related circuits, which provides a plausible bridge between biology and the clinical picture. Nature+2PMC+2

Evidence suggests CRP may help differentiate which treatments are more likely to help which patients. One study reported that lower CRP was associated with better symptom reduction on SSRI monotherapy, while higher CRP was associated with better outcomes with a bupropion-SSRI combination, consistent with the concept that inflammation-relevant biology may moderate response. PMC+1

Recent expert synthesis work explicitly advances the concept of an “inflammatory subtype” of major depression and discusses trial design and treatment implications. PMC+1

PTSD research is similarly moving toward an integrated neuroimmune model.

A major meta-analysis reported that PTSD is associated with higher levels of inflammatory markers including IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, and IFN-γ, while noting important moderators such as medications and comorbid depression. PubMed+1

A widely cited review in Neuropsychopharmacology synthesizes inflammation findings across fear- and anxiety-based disorders, including PTSD, and helps frame the immune signal as transdiagnostic rather than disorder-specific. Nature

TSPO PET is one approach to estimating aspects of neuroimmune activity in vivo, but TSPO has limitations as a specific “microglia activation” marker and must be interpreted cautiously. A major review discusses these strengths and limitations across psychiatric disorders. PMC

PTSD-focused TSPO PET studies are emerging. For example, a 2023 paper examined TSPO signal in occupation-related PTSD with a focus on fronto-limbic regions. Nature

A 2024 study reported a suppressed LPS-induced increase in prefrontal-limbic TSPO availability in PTSD compared to controls and linked greater anhedonia to more suppressed neuroimmune responses. PMC

The bottom line is not “PTSD equals inflamed brain.” The more accurate statement is: immune dysregulation, including altered neuroimmune responses, appears to be relevant in at least some PTSD populations, and may influence symptom burden and response capacity. Nature+1

CRP is not a diagnostic test for depression or PTSD. It is one potential marker that can help flag a possible inflammatory contribution, especially when clinical features suggest an “inflamed” presentation (fatigue, anhedonia, cognitive slowing). PMC+2ScienceDirect+2

If inflammation is “dimming” prefrontal networks, it is reasonable to consider strategies that:

This is one reason translational immunopsychiatry is a high-growth research area, including the evaluation of anti-inflammatory agents as adjuncts in depression. Meta-analyses report antidepressant effects in aggregated data, with meaningful heterogeneity and a clear need to identify subgroups most likely to benefit. PMC+2PubMed+2

Over-the-counter anti-inflammatory drugs are not benign, and inflammation is not always pathological. Any immune-modulating approach should be guided medically, with attention to risk, comorbidities, and the total treatment plan.

At Mind Spa Denver, we routinely see patients with depression, anxiety, PTSD, and TBI-related symptoms who report that they are doing “the right things” but still feel stuck. The inflammation-to-hypofrontality model offers a clinically useful lens: it reframes the problem as a measurable neurobiologic constraint rather than a character flaw or lack of effort.

If your symptoms include prominent fatigue, anhedonia, cognitive fog, or high reactivity despite reasonable treatment, it may be appropriate to discuss whether inflammation screening and a brain-circuit focused strategy could be relevant for you.

Is inflammation proven to cause depression or PTSD?

No single cause explains these conditions. Peer-reviewed evidence supports that inflammation is associated with symptom burden and brain network differences in subsets of patients, and is a plausible contributor to treatment resistance. PMC+2PubMed+2

What is hypofrontality?

A state where prefrontal networks function less effectively, with consequences for cognitive control, emotion regulation, and flexibility. It can present as fog, fatigue, anhedonia, and impaired self-regulation. Frontiers+1

Can CRP help guide treatment?

CRP is not diagnostic, but studies suggest it may be associated with differential response patterns in depression treatment and may help identify an inflammatory subtype. PMC+2PMC+2

What does TSPO PET show?

TSPO PET can index aspects of neuroimmune biology, but TSPO is not perfectly specific and results require careful interpretation. PTSD TSPO PET findings are active research and not yet a routine clinical tool. PMC+2Nature+2

Are anti-inflammatory treatments evidence-based in depression?

Meta-analyses support antidepressant effects for some anti-inflammatory agents, especially as adjuncts, but results vary and subgroup identification remains a key research priority. PMC+2PubMed+2